My Life

by Gertrude Snyder - 1958

|

|

|

|

Would you like to go back...

or return to home page? click here. |

Chapter 5, A Little Bundle from Heaven

Because my life

has been unusual in some respects and because a number of people have suggested

that it should be recorded, I, at 89 years of age, am undertaking to make a

rather detailed description of my experiences, hoping that among my

thirty-three grand- and great-grandchildren some at least will be interested in

this bit of family history.

I, Gertrude Wood

Snyder, nee Gertrude Louisa Wood, eldest daughter of Ebenezer B. Wood and

Rosanna Hardenbergh Wood, was born on December 12, 1869, in the home of my

maternal grandmother, Maria Snyder, Hardenbergh, at 92 Putnam Avenue, Brooklyn,

New York, at that time a pleasant home in a friendly environment which has

changed much in the later years and not to the good.

I was the eldest

of three, -- my sister, Laura Hasbrouck Wood, being two years younger and my

brother, Matthew Hardenbergh Wood, eight years younger. Both are now in their

heavenly home and have been for years.

I have outlived

all my relatives except two cousins, Eleanor Suydam Cortelyou and Edna

Hardenbergh Claus, both of Brooklyn, New York.

My education in

phraseology began at a very early age, fostered by a young uncle who prided

himself on his picturesque speech and did some writing for local papers under

the name of Ryerson Jake.

As he lifted me

into my high chair for my breakfast he would say, "It is a cold morning.

Put plenty of combustible aboard!" I would obediently repeat, "Plenty

bustible board."

Holding me at

the window to watch the trees blowing he would ask, "What is wind?"

teaching me to reply, "Air in motion" and when I came downstairs,

after my nap, newly dressed for the afternoon I would proudly announce,

"This is Gerchude renovated!"

My girlhood was

spent in Brooklyn where I attended public school and for a short time high

school also. My sister had a sad accident to her eye, which was badly cut by a

piece of whalebone snapping into it and putting her into a dark room for a long

period. My mother took me from school to keep her company and I never went

back, but acquired by education from the books I read and my association with a

fine group of young people in the Duryea Presbyterian Church on Classon Avenue.

The newly organized Christian Endeavor founded by Dr. Francis E. Clark found

response in our church and I was a charter member and active for several years.

At about sixteen

years of age I became an out-and-out Christian, uniting with the Classon Avenue

Church and also about this time my love of poetry and my ease in committing it

to memory interested me in what was known as elocution, an accomplishment which

was becoming quite popular.

This also

interested my mother who had much natural ability in amateur theatricals and

who sang like a bird; and she put me under the tutelage of a retired actor,

Gabriel Harrison, and for five winters I studied under him, practicing in the

summers on the farms where we spent our vacations, acquiring a full clear and

flexible voice and a repertoire which seemed to please my future listeners.

About this time

my hones, upright Christian father, whom I loved dearly, was robbed and cheated

by a dishonest partner and to help provide by myself I thought elocution in my

home and for a time in two public schools and each winter gave a recital with

my pupils. I also taught daily in a private school on year. Though I was

successful in the elocutionary line and enjoyed it, my real love was the work

of Christian Endeavor and the Wyckoff Heights Chapel. Our Society was

especially kind to me, sending me as their delegate to conventions in Montreal,

Canada, in Rochester and Utica, New York, and early in the 1890's I was

superintendent of Junior C. E. in Brooklyn. Those were happy days with

congenial companions and I trust some seeds were sown for the Kingdom.

The Christian

Endeavorers of Duryea Church, anxious to do some real Christian work, canvassed

the city for an unchurched quarter and found it on the outskirts where a poor

but thrifty group of people were living with no Christian work being done among

them. Backed by our good pastor and older church members we went out there,

hired a vacant store, gave a free entertainment one Saturday evening and on

Sunday afternoon opened a Sunday School with an encouraging attendance.

What pleasure we

took in cleaning up that store, washing windows, knocking together crude

benches, hanging curtains, etc. I still remember how we made the bare walls

beautiful with Bible verses formed of the lovely colorful autumn leaves, which

we gathered from the woods, waxed and pressed and spelled out he Bible verses

with them.

We divided the

work and to me was given the primary department which met in the kitchen. It

was soon crowded with eager children, many of whom were obliged to sit on the

stationary tubs, and I used to boast of teaching tubsful of children. I called

in the homes, became interested in many families and felt that this was the

work for me but realizing my lack of training I enrolled in the Christian

Workers' Training School in New York and spent a wonderful year there having

the privilege of studying under the fine tutelage of Dr. Adolph Schauffler, who

became a very precious personal friend.

While studying

with Dr. Schauffler I was sent, with a companion, to call at some of the worst

tenement houses in New York, often climbing to the seventh floor through dark

halls, where the only water available to the tenants was from a pump in the

yard downstairs.

I was given

charge of a large Sunday School class composed of children coaxed from the

street by the promise of a stick of candy at the close of the session. This was

known as the "Candy Class." My helper in this work at the Broome

Street Tabernacle was Miss Alice Hawksley, of London, for many years a precious

pal. I remember that when I took my first record of attendance all the bigger

boys gave me false names and addresses lest some trick was being played. Later

when we became friends they confessed this to me.

At the end of my

year of training our Brooklyn Church engaged me as their full time worker at

Wyckoff Heights.

Here I organized

a Saturday morning sewing school and a mothers' club and did much calling in

the homes.

While at Wyckoff

Heights, busy with my work, a cousin of my mother came to visit her. He was a

college graduate starting out on a medical career in Florida but who, while

there, responded to a plea for a missionary to go to China. Because in those

days the Mission Boards sent only ordained men to preach he took a short

theological course, was ordained and then, instead of China, was sent with his

wife, to a virgin field in the heart of the Belgian Congo, Africa. Here he

helped to start what has proved a marvelous work among the Balu a and other

tribes in that region. He and Mrs. Snyder left America in 1891 but after a very

few years in this malarial climate Mrs. Snyder died and is buried near

Leopoldville. Her husband soon came home on furlough and visited his Brooklyn

relatives.

Before he

returned, at the end of his year's furlough, he asked me to go back with him as

his wife, but I did not feel ready to link my life with his and he went back

alone.

I had my full

share of young friends and offers of marriage but was still heart free.

However, we corresponded and as I came to know him better and to become

interested in the fine work he was doing, my heart inclined more and more to

his request.

My years as a

worker at the Wyckoff Heights Chapel, built for us by a wealthy church member,

Mr. Alfred J. Pouch, were very happy ones. I had a band of loyal friends and

co-workers without whom I could have accomplished very little. Among them was

George Moffat who led the singing so heartily, Frank, his brother, who worked

with the boys, Louise and Gertrude Williams, Fannie and Ida Williams, Bessie

Gilbert, Will Halsey, Arthrur Chruchman, James Cruikshank who played and sang

for us, Joe Eastmond and others too numerous to mention. My sister Laura had

charge of a group of junior girls.

In 1898 feeling

that I had little knowledge of what to do in cases of illness or in baby care,

I applied to the Brooklyn Homeopathic Hospital for a three years course in

nursing.

Dr. Orando S.

Ritch, my doctor since childhood, being one of the head doctors there, I

entered October 1st, under very auspicious circumstances and enjoyed a year of

interesting and profitable training. Being in a sense a protege of Dr. Ritch I

was accorded a number of privileges and saw considerable service in the

operating room.

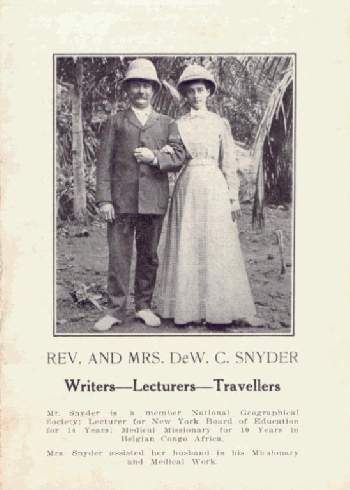

In the meantime,

before the year was ended I had become engaged to the Reverend De Witt Snyder

who was sent by the Southern Presbyterian Mission Board under which he worked

back to America to superintend the building of a much needed mission steamer

for the rivers of the Congo. The Sunday School children of the south raised

$20,000 for this project and Mr. Snyder came to Virginia to see it built and

tested on the Potomac River.

He was reluctant

to return again alone to his field and so, partly because I was marrying a

medical man (and perhaps a little because after our examinations at the end of

the year I had the good fortune to stand at the head of my class the doctors

voted to set aside the contract for the remaining two years and allow me to

accompany Mr. Snyder. Accordingly I left the hospital October 1, 1899 and went

to Saugerties on the Hudson to the home of my aunt Gertrude Hardenbergh, who

assisted greatly in outfitting me for my new work.

So closed a page

on the book of my life, and a new one was turned which was to prove strange and

full of sunshine and deep shadows.

On the afternoon

of October 10, 1899 I was married to the Reverend De Witt Clinton Snyder in the

Classon Avenue Presbyterian Church, Brooklyn, New York, where I had grown up:

married by my dear friend and teacher, Dr. Adolph Schauffler, with the pastor

of the church, Reverend David Burrell, assisting. It was a lovely wedding,

enhanced by arrangements made by my friend Helen Voute, who brought a band of

children from the Wyckoff Heights Chapel to walk before me and scatter rose

leaves in my path as I came down the aisle on my husband's arm.

My ushers represented

four phases of my life -- my brother Matthew, my home life; Conrad Keyes, my

church life and Christian Endeavor; Frank Moffat, the Wyckoff Heights Chapel;

and Dr. John Black, my hospital service.

At the reception

in the church parlors the children marched in to give me their good wishes and

the tiny boy leading them put a big bouquet in my hands saying, "Here,

Miss Wood!"

Perhaps a

granddaughter would like to know about the wedding dress. It was made of very

pretty ecru or pale gold poplin, trimmed with a lovely shade of violet velvet

and a collar and cuffs of gold colored silk thread crocheted by nuns in Ireland

and purchased by the groom on his way home.

After the

reception we went to the Holland House in New York for dinner and spent the

evening in an art gallery. A few days were given to visiting friends of my

husband in Richmond and Charlottesville, Virginia, after which we returned to

New York. The 25th found us on board the ocean liner "New York"

waving good-bye to a host of relatives and friends.

Miss Helen Voute

brought a large group of the Wyckoff Heights Sunday School children to see us

off and they sang "Onward, Christian Soldiers" and "God be With

You Till We Meet Again" as we steamed away.

On board with us

was the completed mission boat which Dr. Snyder had come home to have built. It

had made a trial trip on the Potomac River, then was taken apart, put up in

packages weighing not more than sixty pounds each and shipped with us to be the

bearer of good tidings on the Congo, Kassai, and Lulua rivers in central

Africa. Sixty pounds is the limit a native will carry on his head on a caravan

marsh.

Steamers were

not as fast in those days as they are today but we had a delightful voyage,

landing in London where we found comfortable lodgings and made connections with

my husband's good friend, Mr. Robert Whyte, the head of a large wholesale house

in Houndsditch, Bishop's Gate. He proved a delightful friend, entertaining us

in his home and helping us select our equipment for the Congo. He was a Scotchman

and I can hear him yet, as he stood in front of his glowing fireplace, say,

"Come awa', Mrs. Snyder, come awa'."

We made London

our headquarters for six weeks and took side trips to the Netherlands, visiting

the Hague, Leyden, Delft, Scheveningen and Amsterdam; also the Belgium, seeing

lovely Brussels and other places and going to Scotland for a view of Edinburgh

and the Firth of Forth. In Manchester we did much shopping for what was then

known as calico for native trading and here I found, after much searching, a

rocking chair, almost unknown in the British Isles but unearthed from the

corner of an attic and eagerly seized upon. I might add here that this same

rocker was not delivered to me in my Congo home until eleven months later.

Well, I was privileged to enjoy it a few months at any rate and it was a

comfort to me.

In London I saw

my first movie or cinema, a Navy picture; and I still remember those young

sailors running down stairs answering the call to breakfast. It seemed a

wonderful picture. Recalling our London sightseeing, here is an extract from a

letter written to dear Aunt Anna Hardenbergh in Brooklyn.

" We have

visited the grand old Westminster Abbey where one could spend days studying the

beautiful monuments and recalling English kings and queens. We attended

services in the

Abbey one afternoon and last Sabbath we heard Dr. Joseph Parker

preach. One day

last week Ian McLaren spoke in his church and we went and greatly

enjoyed him.

"We have

crossed London Bridge many times, have seen the beautiful houses of

Parliament, the

old London wall dating back to Roman days, visited the National Art

Gallery, driven

through streets whose names are familiar to readers of Dickens and

other English

writers -- Paternoster Row, the Strand, Oxford Street, Threadneedle

Street, etc. --

have seen the old Newgate prison, the beautiful government buildings, the

horse guards and

hosts of other interesting sights. It has rained almost every day and

even when the

sun shines it is so sickly and pale that one does not recognize it as

sunshine. It is

not cold but damp and raw and the streets are never dry."

Mrs. Lucy

Sheppard, whose husband was in Luebo, came across the Atlantic with us. She was

very pretty and bright, a lovely singer and would certainly be a pleasant companion

in the jungle. She took a boat ahead of us for Luebo (pronounced Loo a' bow).

At this time I

greatly enjoyed shopping for our new home, purchasing bedding, dishes, chairs,

kitchen utensils and other necessary items; and I looked forward to the pleasure

of fixing up my future dwelling place. On December 16th we crossed the North

Sea again, this time to Antwerp where our Congo steamer, the Stanleyville, lay.

My, it was cold! Decks were ice coated, pipes frozen, not a bit of heat

anywhere, even the big steamer rug, I still shivered that December morning

until heat was finally obtained, pipes thawed and we steamed out into the

Scheldt River, really on our way to the dark continent.

The memory of

that wonderful voyage is still with me. Out of the river into the North Sea,

then through the English Channel into the turbulent Bay of Biscay and so into

the broad Atlantic Ocean, on we went, a glorious trip of three weeks. Cold was

left behind us and in a week's time we were opening trunks to get out summer

clothing. Our genial Captain Sparrow, a young Englishman, did all in his power

to make our voyage a pleasant one. I was not the only woman on board. A Belgian

whose husband was working in Boma was on her way to join him but, alas, the

ignorance of each other's language prevented any conversation and we could only

smile at one another.

At the Grand

Canary Islands the steamer dropped anchor and in one of the big row boats which

was soon at our side we went ashore. A pony cart took us around the island and

we stopped to buy, for almost a song, a huge basket of oranges, lemons,

cucumbers and other fruits and vegetables and a pair of real canaries to

sweeten our new home with song.

The little trip

to the Grand Canaries provided us with the only bit of excitement on an otherwise

peaceful voyage and that a very brief one. The wind had changed while we were

sightseeing and the sea was rough with waves so high that the ship, anchored a

mile out, was visible one moment, invisible the next, as we rode the crests or

sank into the troughs. Our six stalwart rowers pulled hard on their oars but

about half way out suddenly an oar lock snapped throwing the rower from his

seat and twisting our little craft completely out of its path and into the

trough of the sea. I was flung, with my cage of birds, across the boat into the

lap of my husband who sat on the other side. However, no harm was done. The

alert head man had the damage repaired almost immediately, we were righted, and

proceeded safely on our way.

When we reached

the ship the captain was standing at the head of the ladder, spyglass in hand.

He had been watching our progress and was prepared to send help at once if it

were needed. As I mounted the ladder he stretched out a helping hand and paid

my American sisters a compliment saying, "I have always heard that

American ladies were brave." To me it was just something to write home

about. I shall never forget those beautiful moonlit nights nor the

phosphorescence dancing on the water as if a thousand fairy boats were cruising

about. We saw whales spouting, porpoises leaping, and as we crossed the Equator

Father Neptune came aboard with his trident and his train of attendants.

However, before that we made a brief stop at Sierra Leone -- Africa at last!

Here we saw Moslems in their long white robes, natives with almost no robes at

all, Europeans and other races; and as we rounded the big bend somewhere along

the Gold Coast were the Kroo boys diving for the pennies thrown overboard or

coming on board to help with the cargo.

At the Equator,

that famous imaginary line with its initiatory rites into southern waters,

Father Neptune came among us followed by a grim looking doctor, the barber with

his big whitewash brush, a sailor with a pail of flour paste lather and an

anticipatory grin. Woe betide the hapless victim who is making his first

crossing. Into the chair perched on the edge of the tank he goes, is given an

absurd diagnosis and a bitter pill by the doctor who shakes his head

mournfully, is well lathered with the whitewash brush and at an unexpected

moment over backward goes the chair dumping him head first into the tank of

cold water. Here he flounders around looking for a way of escape but hindered

at every turn by a stream of water from a huge hose, an effectual bar to

progress until the Captain mercifully calls a halt. My husband had crossed

before and suffered the ordeal and our gallant Captain took charge of me,

lifting me into the chair, touching me cheeks with a bit of the lather, wiping

it gently off and lifting me down again -- ordeal over. And so on down the west

coast between five and six degrees to where the mighty Congo River rushes out

into the ocean showing its muddy waters about 300 miles out, I am told.

Here we are at

Banana, a spit of land on which we stand with the ocean on our right hand, the

Congo on our left and I see my first coconut palms, always bending gracefully

toward the water as if they were athirst. Coconut palms, God's wonderful gift

to the African, supplying his every need! Here we meet opposition -- sandbars

and eddies an slowly and carefully we inch our way up the seventy miles to the

little tropical town of Boma, at that time the capital of the Belgian Congo

Free State. This took us from January 4th to the 7th, at one time being obliged

to lighten our cargo by 180 tons before we could cross an enormous sandbar.

This was an interesting time to arrive in Boma. For a year and a half, Belgian

engineers had been at work on a railroad planned to run one hundred miles into

the country. Twenty-one and one-half miles of track had been laid and an

official opening was to be held. We received invitations, written in French, to

participate in the ceremonies and accordingly with the ship's Captain, doctor

and chief engineers we mingled with the crowd the morning of January 10, 1900

and took our seats in the governor's car, seating twelve.

Set down in an

American railroad station this would be looked upon as a toy train decked with

Congo flags showing a gold star on a bright blue field -- some small boy's

Christmas present. But when the whistle blew away we went. Such a winding way!

Such interesting country! Winding around hills, twisting around horseshoe

curves, crossing deep ravines or narrow muddy streams; sometimes papyrus waved

in the swamps, sometimes pink or purple orchids bloomed, sometimes grass grew

ten or twelve feet high.

After about ten

miles or so we entered a forest of tall palms, enormous baobab trees, pawpaws,

cottnwoods, ash, and other trees, a curious sight being tall palms hung with

birds' nests, 200 or 300 in a tree, looking at a distance like fruit.

We were two and

a half hours traveling the twenty-one miles but when we reached Luki at the end

of the line we found a goodly company assembled, a brass band and plentiful

refreshments. We had the honor of being the only Americans and I of being the

only lady among the 250 guests. Returning we made the trip in better time -- on

and one-half hours. There were two trains a week, going and returning the same

day -- Mondays and Thursdays -- fare, round-trip, $7.50.

Cargo from our

ship was unloaded by a slave gang, a sad looking group of prisoners shacked

together, who moved like snails and took seven days to do the work our

stevedores would have done in one. Then from Boma we steamed on twenty-five

miles or so miles across the river to Matadi, named for Henry M. Stanley, the

rock breader, and where we were comfortably established in a Swedish mission

house -- a real tropical home. Here we said goodbye to a few luxuries, although

our good Captain Sparrow preserved one a bit longer for us. He presented us

with a huge block of ice, which when well wrapped in a blanket lasted us a week

and for which we were truly grateful.

From

Leopoldville, some 280 miles north of us, down to Matadi the Congo rapids dash

down some 2,000 feet making navigation impossible for the small river steamers

so another single track narrow gauge railroad took us on our next lat.

Time is nothing,

or was at that time. Trains ran when convenient to all concerned and so we

waited eight days for one to pull in and be ready to start out again on its two

days? journey. The first nights' stop was made at 6:00 p.m., steep in a little

half way house, breakfast of sardines and crackers and what was called coffee

and at 6:00 a.m. we were off again. Slow, easy going, dirty, wild, heathen

Congo land! The railroad, at that time at least, was a money making project.

First-class fare $95, freight 10 cents per pound. In the first-class coach

windows were without sashes, glass or blinds. If it rained one got wet. If the

sun shone brightly it was just HOT!

But what a

wonderful journey! Over the tops of mountains the first day, then through dense

forests the next, seeing no human habitation, rarely a human being. At the end

of the second day, just as the sun was setting we found ourselves in

Leopoldville on the shores of Stanley Pool where the river widens out into a

great lake some fifteen miles across.

Leopoldville,

today a bustling modern city, the capital of the Belgian Congo, then a tiny

village where a few white traders or engineers lived and native huts clustered

about.

Here in true

African style we waited eight days for a river steamer to being us to our

journey's end and at last on the morning of January 29th we bade our kind

missionary friends good-bye and started once more on our travels.

I wish I might

paint you a vivid picture of the State steamer, the Ville du Bruxelles, as we

came to know her after spending thirty-seven days aboard her. In size about

eighty feet by twenty, dirty, out of repair, slow, ill-kept she rises before my

mental vision like some horrid dream.

On the upper

deck there was barely room for the twelve passengers to place their chairs and

sit in comfort. Here, too, were the cabins. Our room, eight feet by five, was

assigned us. There was nothing furnished but a small shelf and a few nails to

hang clothes up on. It is needless to say that we lived as much as possible on

deck, for when our various steamer trunks and other baggage had been deposited,

the room was no longer empty.

One small cot

bed was all we could put up and my husband was obliged to make himself as

comfortable as possible in his deck chair (which would stretch out quite flat

if you did not move too suddenly) during those weary, hot, mosquito infested

nights. On the deck below us natives were huddled together in company with

goats, dogs, pigs and chickens. It was here, too, that our food was cooked by a

native "boy." The wood gathered at night by the Bengalese was chopped

for the engine's fire. The table, set upon the deck, was spread with unbleached

muslin and when we had been on the boat eighteen or twenty days this piece of

cloth accidentally caught fire and necessity furnished us with a clean cloth.

The napkins at the beginning were strips of the same material half a yard by

the width of the muslin. These gradually diminished in size as the days went

by, the most soiled portions being torn away to obviate laundering.

Our food

consisted of goat's meat, chicken, pork, soup, yams, and coffee of which my

husband said one must drink three cups to get one. There were pancakes and

cake, wonderful to see but more wonderful to digest.

It was a slow

journey. Often we stopped at two in the afternoon and remained on the edge of

some deep dark forest until six the next morning. No traveling was ever done on

the rivers at night. The steamer carried us within three days of Luebo, our

destination, but then turned aside and took us on a thirteen day trip up the

Sankura River to Lusambo, an important state post.

In spite of the

discomforts of the trip no one with an eye for the beautiful and a heart

responsive to the wonders of God's creation could fail to enjoy thoroughly the

beauty of the scenery on either side of the river. New and magnificent

varieties of trees, great vines making dead trees lovely imitations of old

world ivy clad ruins, feathery palms large and small, and here and there new

foliage of vivid scarlet lighting up the soft rich green.

Here I made the

acquaintance of hippopotami, elephants, monkeys, crocodiles and brilliantly

plumaged birds; and of strange dark skinned brothers and sisters for whom

Christ died and who know it not.

Little moths

came nightly to visit us whenever or wherever there was a light and one fished

them out of the soup by the dozens, kept the glass of water carefully covered,

and examined every mouthful of meat in order not to swallow more of the little

creatures than necessary. Strange how insignificant little pests can make even

eating difficult, isn't it?

Let me introduce

you to Katalia who became our personal boy for the trip. He had been taken to

the coast by Mr. Sheppard when he went down to meet Lucy, placed in a Dutch

Trading House to learn to cook and return with us. He was perhaps twenty of

more years of age, had left a wife in Luebo for whom he said his heart was

crying, was a real Christian and came nightly to our cabin for a little

service. He sometimes prayed that I might have a good tongue for the Baluba

language. He cleaned the cabin, washed and ironed and was a very willing

worker. He often thanked God that I was going to Luebo, for the people needed

anew Mama. When I learned a few words and could use them correctly he was as much

pleased as if I had given him a present.

It was quite

cool mornings. Once we saw two huge crocodiles sunning themselves on a sandbar

and hippo heads popping up all around us.

Both the Congo

and the Kassai rivers have the yellowest waters I ever saw. It was almost

impossible to tell by sight whether the water in our wash basin was freshly put

in or had been used by a dozen people. One morning I woke to find the pitcher

had a topping of tiny red ants and worse still that my pillow was alive with

them, my neck and hair also. My unfeeling husband said that I was truly radiant

that morning. But the men had their troubles, too. One day just after dressing

and going outside my man began to feel uncomfortable and an examination showed

his undershirt swarming with the little creatures. My sister Laura would

probably say, " Such is life when you don't use Pears Soap."

One night we

evidently obstructed a path by which hippos came ashore for supper, for all

night one hung around grunting and scolding, though mercifully doing no damage.

The Kassai River

is almost as large as the Congo, has a very strong current against which we

pushed and strained, often finding ourselves stuck on a huge sandbar. Then all

the natives must go overboard to push and pull the boat off.

A pretty sight

seen one day was an old dead tree floating down the river with eighteen or

twenty little birds about the size of sparrows, but blue and white, sitting in

a row upon it, apparently out for a sail and thoroughly enjoying themselves.

The picture was pretty enough to paint were I an artist.

I recall vividly

a stop we made at a trading post. The trader came aboard looking so delighted

and saying, "I have not seen a Madame for three years! What can I do for

Madame?" He invited us to go ashore which we gladly did, walking about his

well kept house and grounds and accepting his hospitality. At dinner we were

served hippopotamus steak which my facetious husband said was so tough you

could not get your fork in the gravy. When we left, the trader presented us with

a big basket of fruit and vegetables, a welcome addition to our diet.

Later we stopped

at another trading post and here an excited native rushed up to Dr. Snyder,

dropping on his knees before him crying, "Ngangabuka, take me! Take

me!"

To Nagangabuka's

surprise it was one of the Christian boys from Luebo who had been captured by

Bula Matadi (the State) and forced into servitude. Needless to say Nagangabuka

made satisfactory arrangements for his release and he left the trading post

with us, the most grateful young man one could wish to see.

The name

Ngangabuka, really meaning witch doctor, had long ago been given to my husband

and after this I will so refer to him.

So the long

thirty-seven days' journey drew to a close and one happy day, March 6, 1900 our

boat blew a loud salute to the missionaries and natives at Luebo and edged

carefully up to the little wharf.. On shore what a crowd to welcome us and what

a shout of "Mouyo, Ngangabuka" went up as the loved missionary

returned to his field and those who called themselves his children.

Dr. Morrison,

the beloved follow worker; Mr. Vass, young and energetic; Miss Thomas and Miss

Fearing, the two splendid colored women from our Southland; and faithful Mr.

Phipps were there and what a welcome they gave us.

A hammock was

provided for the new Mama and two willing bearers carried her swiftly up the

mile long road to the new home awaiting her and a new life begun 10,000 miles

away from the place of her birth, -- the long trip safely over.

When I arrived

at Luebo the tragedies of the early days were over. Stolen goods had all been

returned; threats of violence, the danger to life and property had given place

to trust, respect and affection, so that for Ngangabuka's sake the new Mama

received a warm welcome and loyal service. A white man with love in his heart

for his dusky brother had opened the door of a happy home and the way was made

smooth and easy for her.

Kasubetu --

"our little house" -- what a dear place it was! For the sake of

brevity and euphony as well, many Bautu words were contracted and what really

was ka nsuba Tu wetu became kasubetu (pronounced car sue bay too). We thought

it such a pretty name; though judged by Congo standards it was no a small

house, but almost a castle.

Mganga had seen

it built before he left and had put in some necessary furniture. Mr. Vass had

built a cupboard for my dishes and native hands had made it clean so we settle

in it at once. But, alas, after a day or two Ngangabuka came in with a severe

attach of fever, which put him to bed and effectively prohibited any help with

the language. I struggled with it, and the houseboys and girls did their best

to understand and aid me. Dr. Morrison stayed nights beside the sick bed and

Jake slept under the dining room table to be at hand in case of need. In a week

the fever was over and all went well. The house began to look like a home and I

began to understand Congo ways and needs.

How my husband

laughed at me when, after everything was in place, pictures and curtains hung

and books arranged, I said, "If only someone could come in and see

it!" His comment was, "Isn't that just like a woman?" Well, I

could at least write home about it and later many pictures were taken and sent.

The house

boasted three good-sized rooms -- dining room in the middle, our bedroom to the

right, a sitting room to the left. Our big four poster bed carried the

indispensable mosquito net, our towel rack was an elephant's tusk, our clothes

closet a curtained off corner. Frequently spiders as large as tea saucers sat

on our walls, little lizards ran up and down the window curtains and we always

listed carefully for sounds of the termites before lighting our candles. Our

house children said we had cloth enough in our bedroom o clothe a whole

village, and I suspected it came near the truth. To the natives we were

millionaires.

House servants

were so necessary and so cheap that we had ten who were paid weekly in salt and

cowrie shells and, once in three months, given two yards of calico. Malindola

and Mudimba were our outstanding couple, both fine sincere Christians, Mudimba

especially excelling in language work. Katalia or David was a good cook, quick

to observe our likes and dislikes, Dick or Jake, pronounced about alike, jack

of all trades, master of none, but devoted and loyal. Kaphinga, his wife; Madi,

the garden helper; and Undia, his wife, a gentle motherly girl; Mbun, the

cook's assistant; and Dufanda and Madinki, two boys of about ten years who

waited on tale and ran errands -- each one was an interesting character study.

Real work was new to these children of Mother Nature who provided lavishly and

freely for them. Often I would find Kaphinga stretched out in a corner of the

verandah half asleep and when I inquired about it she would reply, "Just

tired for nothing, Mama."

Our garden,

planted with seeds brought from home, yielded us tomatoes, onions, peas,

lettuce and cabbage, beans and yams, and a huge squash grew wild. Corn was on

our table every month during the year. Our storehouse, a dark enclosed corner

of the verandah, was well stocked with flour, rice, and cane of many varieties,

so we fared nicely as to our cuisine.

For dessert

there were always bananas, mangoes, pawpaws, guavas, and passion fruit, with a

big pineapple patch at hand. Chickens and eggs were purchased from the women

who came daily to sell. Katalia proved a good cook and Dufandia a great success

as a table boy.

One day I made

jello and gave the dish with the liquid in to him to set very carefully and

well covered on the he floor of the storeroom. The next day Ngangabuka asked

for it and Dufanda brought it so carefully that he might not spill a drop. What

was his surprise to see Mgangabuka tip the dish and the contents remain solid

and firm and he exclaimed, "I put it away week like water and now it is

strong!" "How is it?" asked Ngangubuka, but Dufanda shook his

head. "That," he said, "is a palaver for Mama's brain."

In daylight every

moment was filled, beginning soon after sunrise with the tolling of the rising

bell, followed soon after by the call to worship in the little church and the

day began with praise and prayer. The average attendance was two hundred or

more, many coming from surrounding villages where the gospel had been preached.

After this the pre-breakfast tasks began. Mr. Hawkins gave out the workmen's

individual duties. Mgangabuka found many patients waiting for him at his

pharmacy. The ladies began breakfast preparations and by seven o'clock the meal

was over and each missionary was free for an hour of meditation and prayer.

Then our house

children gathered for their special word of help or request or assignment and

one might have heard Malindola earnestly pry that their hearts might be made as

white as Ngangabuka's shirt -- the whitest thing she knew.

By eight

everyone was at his special task. Mr. Hawkins at his brick making, Mgangabuka

at his printing -- his devil and his pi, Dr. Morrison his language study and

dictionary.

For a printing

press came to Luebo in May, unassembled, of course, even though no one knew a

thing about presses nor printing. However, inside of a week Mgangabuka assisted

by Mr. Hawkins succeeded in overcoming assembling difficulties and now let me tell

you the rest in his own words.

"The Type

had become sadly mixed during the long journey from England and it was no

little

job to get them

in their proper places. No one knew the system of arrangement so we followed

that on the keyboard of my typewriter. The Ink Roller. We found

this instrument tightly encased in tin and wondered why so harmless looking an

instrument should be so closely guarded. We carefully adjusted it in its handle

and laid it on the ink slab while busying ourselves with other work. In the

meantime that roller, under the caressing influence of our genial and

warmhearted sun, began to spread itself and disclose the fact that it also had

a sweet character, in proof of which it became sweet on the ink slat -- indeed

quite stuck on it and the slab, poor ;thing, had more molasses clinging to him

than was seemly in a staid old stab. When we returned to our roller it was a

puddle of glue and molasses, the joke being that it was made especially for the

African climate.

"Something had to be done and quickly. The nearest place where one

might purchase a roller was London, from which place it would take from four to

six months to get it, so I made a mold and reformed the wayward thing. Since

starting to print this little paper I have remolded that roller five times. Setting

Type. Our first attempt at this took nearly an hour and the result was in

part as follows: "na, rydsorP - naoriceanA, etc. Perseverance, however,

won the day and we have succeeded in printing a twenty-four page school book

now in use in the school.. Our fonts of type are so small that I have had to

wash, reset and distribute them six times during the printing of this

paper."

Ngangabuka's

interest n the insect life of the Congo gave us many a pleasant busy evening as

we worked on the collection he made for the Smithsonian Institution in

Washington. We separated and encased in folded paper containers lepidoptera,

neuroptera, homoptera and whatever other opteras there may be. Under his

tutelage I became fairly helpful. Other evenings he read aloud to me from our

small supply of books as I sewed on garments. We learned of "The Rise and

Fall of the Dutch Republic" and of "Brave Little Holland and What She

Hath Taught Us" and increased our respect for the land of our forefathers.

Once a week we missionaries met together for prayer and Bible study.

On one such

evening as we met in our sitting room we had an unexpected and unwelcome

visitor. A steamer had come that day and considerable cargo was piled on our

veranda, and as Ngangabuka was reverently reading from the Bible a fairly large

snake evidently hidden somewhere among the bales slowly trailed its length into

the room. You may guess that I interrupted the Bible reading but I did it as

quietly as possible and Ngangabuka, taking in the situation, picked up a small

tusk which was near by, made short work of our visitor, threw it out and calmly

resumed his Bible reading as if nothing unusual had happened. Only one other

time did a snake invade our domain. One night our precious little canaries were

attached and one killed. The commotion awoke Ngangabuka who went to the rescue

a bit too late to save papa bird, but I slept on and he did not let me know the

real cause of death until all possibility of another attack was past.

I was the

possessor of four beautiful parrots, large gray birds with bright red tails,

which wandered about freely and at four o'clock every day invariably found me

wherever I happened to be to receive their afternoon treat of peanuts. Nan, the

most affectionate one, would climb to my shoulder and amuse herself pulling the

hairpins out of my hair. I brought her home to America with me and she learned

to speak and to mimic sounds quite well.

Surely the

natives had many clever ways. One day Dick came to his "tata" (father

Ngangabuka) holding a much bent and forlorn looking tin cup and plaintively

remarked, "Look at the bright new drinking dish your parrot has and look

at what you child has to use." You may imagine his bright new cup was soon

forthcoming.

Mbua was my

devoted watchman. Ngangabuka had given him a task when we first arrived to

watch Mama and never let her go out of doors without wearing her pith helmet.

Not always remembering it myself I would hear the worried cry, "Chifulu,

Mama, Chifulu!" and Mbua would appear with the necessary headgear.

A frequent

visitor in our home was our much loved follow worker, Dr. William Morrison. He

would come in with his pet monkey, Twobits, on his shoulder, not always as

welcome a visitor as his master. I remember how deftly Twobits seized a glass

of water from the table and in the twinkling of an eye was seated on the top of

the bedroom door ready to spill the contents on anyone who objected to his

actions. I also remember how he espied a large box of empty bottles for use in

the pharmacy and how rapidly the corks came out and flew in one direction, the

bottles going in another. Yet when a baby monkey was sent to us and we put it

in Twobits' cage how lovingly her arms were opened to receive it, how tenderly

it was clasped to her breast and cared for day after day.

Many stories

might be told of native sayings and of our mistakes in the language; and at the

risk of being thought egotistically personal I would like to tell you of an

episode which occurred on our veranda one day which was to us both touching and

amusing. I stood on the porch as old Chief Kuata, accompanied by several of his

men with pretty well made baskets to sell, approached and began to bargain. Not

feeling equal to the palaver I knew would ensue I called my husband from his

work in the house and he, coming out, stood beside me and took my hand. This

was an unheard of gesture of friendliness in Congo and Kuata quick to notice it

exclaimed, "The liking of Ngangabuka for Mbombasham exceeds!" or is

very great. There is no word for love as we know love in the language of the

Bantu. My husband mischievously trying to still further impress old Kuata put

his arm around me and drew me closer, to which Kuata responded, "The

liking for Mblmbasham by Mgangabuka exceeds the liking of Bakete men for Bakete

women" and when Ngangabuka drew me closer and kissed me the poor old chief

exclaimed, "The great liking for Mbombasham by Ngangabuka exceeds all

the liking of all the Bakete men for all the Bakete women,

"and throwing up his hands he sank in a heap on the ground overcome with

amazement. Love, God implanted in every human heart but sleeping her under

blankets of selfishness, ignorance and superstition, must be awakened and

activated; and ours the task! What a challenge!

And slowly but

surely it did awake in many hearts. During the weeks the church grew in

numbers, the catecumen classes were filled and on Sundays not only seats but

floors and glassless window openings were filled with earnest worshippers.

Mothers brought their babies, minus clothing, and nursed them when they cried;

the houseboys came in cast-off missionary shoes or one piece of a suit, proud

in spite of heat and questionable fit. It was a time of great ingathering, and

the Lord's blessing was with us abundantly.

One of the tasks

assigned to me was correspondence with the churches at home which were

contributing to our support, and sending articles to the missionary magazine

published by the Board. I wrote many letters to gracious friends telling of the

progress of the work and of life in a dark continent. The Brooklyn Eagle also

published some of my articles.

Such she was,

loaned to us for a very little while, only nine short months. After she left us

I wrote the story under the title "A Little Life for Africa" and I

would like to incorporate it here, for it perhaps is as well done as I can do

it, and only one or two of the original copies remain. I would like my young

grandchild mothers to have it as I wrote it then back in 1901.

A Little Life for Africa

On the top of a hill in the little settlement of Luebo, in the heart of

the Congo Free State, Central Africa, stands a picturesque little house known

as Kasubetu (car soo bay' too), "our little house." A dear little

home indeed to the two missionaries who dwelt under its roof and sought to make

it an object lesson to the natives who came daily to see how the mputu people

lived and how the white man provided for and treated his wife. "Ah, they

would say in wonder at his thoughtful care and tenderness, "his love for

her exceeds. it is not so with us."

Into this happy home there came on the eighteenth of August 1900 the

sweetest of heavenly gifts to two loving hearts, a wee sweet maid with big

brown eyes that opened on a strange world. A white baby was a wonderful thing

to see and daily the little house was filled with eager visitors: men, women

and children, who wondered at her fairness, marveled at her clothes and took

her to their hearts at once. "Thank you, Mama, for the baby," came

from many lips. "You have done well."

On the morning of her third day in the little house a troop of men and

boys, a hundred or so in number, entered the missionaries' yard announcing that

they had come to dance for the baby. so earnest was their intention that they

were allowed to dance in their strange way, accompanied by native drums,

brandishing their spears, led by the old village chief, Kuata, for fifteen

minutes or so near the bedroom window while baby was wrapped in a blanket and

carried out on the veranda for them to have "just a peep" at her.

Then with a present of cowries whey were dismissed.

The old chief, Kuata, often visited the wee maid bringing her a chicken

and a large square package of native salt and naming her Nkendi after his

favorite wife.

Many eyes watched the little one?s steady growth noting the regular

feeding, the careful cleanliness, wondering because she slept in her own wee

bed and as she grew older enjoyed her daily warm bath, instead of screaming

during the process like their own babies, who strongly object to the cold water

as it is poured over them and sun and wind made to do duty as towels.

In the first days of their joy over the treasure God had given them,

the father and mother knelt beside the little crib and dedicated the baby to

Christ and to His work, asking that if she grew to womanhood she might be a

missionary of the Cross, perhaps in that very field; and that day by day the

little life might leave its impress for good on the savage ignorant lives

around it. When the day for baptism in the little church came, hundreds of dark

eyes saw the minister take the child in his arms, heard him give it to God, and

father and mother promise, in the native tongue, to teach their little one the

things of the Kingdom.

Many were the plans made for that little child, many were the hopes

centered upon her. She would learn the native language as no missionary had as

yet been able to do, absorbing it unconsciously from the people as children do.

She would teach them of heavenly and earthly things in her sweet baby way; she

was to be a perpetual object lesson. The mother longed for the hour when she

would lisp her first prayer that those dark mothers might come and see and hear

and so learning teaching their little ones.

The native fathers leave the care of the babies entirely to the

mothers, displaying no affection for them and never dreaming of relieving the

woman of her burden as she goes about her work. The missionary father, from the

hour of her birth, taught his love for his child, caring for her as tenderly as

a woman, relieving the mother's arms as often as possible and always when baby

was given her daily walk carrying her with such evident pride and pleasure that

the lesson was not without its effect on all who saw the two.

When the father and mother went about among the many huts and villages

surrounding the mission taking baby with them there was never any difficulty

about an audience. Men, women and children flocked to see the white child and

if one woman were allowed to hold her the rest settled down quietly to hear the

missionary's message. What matter if baby came back to her mother with her

little dress streaked with palm oil and red dye? She had helped in that little

meeting.

From back in the Baluba country came men on trading expeditions and

they never failed to call on little "Bawote" as they named the baby.

Every trader on the Kassai and for hundreds of miles on the great Sankura River

took an interest in the white baby at Luebo and instances might be cited of the

softening effects of that wee life on those who had come to Africa for

money-making alone.

An incident, which touched the parents' hearts, occurred one evening in

December. Mother and baby were seated just within the house door watching for

the father to come to early tea. When he came he brought a native woman with

him who said she had traveled many, many days to see Ngangabuka's baby. Before

baby's birth she had been cut in a fight and had come to the mission for

treatment remaining long enough to learn the sweet story of Christ, accept Him

and unite with the church. Then she had gone away with her people. Ever since

hearing of our little one's arrival, she had been asking God to let her return

to see it and that very day she had prayed for her welfare. Her delight at

actually seeing the baby was unbounded. Sitting down on the floor in the native

way she said, "And now Nzambi has let me see her!" and began talking

in low soft tones, laughing up at the child even while tears stood in her eyes.

And baby, as if appreciating the situation and probably attracted by something

in the smiling face, cooed and laughed aloud, delighting her admiring visitor

beyond expression. Then with tears she told us how another tribe had stolen her

own two children and she had no idea where they were.

For the first five months of her little life baby seemed so well, so

happy and bright. Then the parents noticed with anxious dread which they

scarcely expressed to one another that she was becoming anemic and was not

gaining in weight. Invited by the mission committee to go to Leopoldville 800

miles nearer the coast on important business the missionary consented to go

taking wife and child in the vague hope that the journey might prove

beneficial. But traveling on Congo State boats is far from luxurious and this

one proved even worse that usual. After eleven days' journey with the rapid

down current, it was bliss to reach Leopoldville and be once more in a comfortable

house. Here, in spite of every care and effort the little one continued to

fail. Every day she grew paler, sometimes having fever and ere a month had

passed the last resort was determined upon -- to take her with all speed to

America.

Accordingly on April 6th the heartbroken father bade wife and the sick

little one good-bye on board the Antwerp steamer, returning to his lonely home,

while the mother gave every thought and effort to battling with the fever and

increasing weakness of her darling. These were eighteen long sad days but as

they drew near Antwerp hope sprang up at the thought of good medicine and the

comforts of civilization. God knows best. He understands what we cannot. The

nearer the steamer approached Antwerp the more rapidly the little life ebbed

away and at eight o'clock in the evening of April 24th, at the very moment the

engines ceased their work the machinery of a wee life stopped also and little

Anna Gertrude slipped from her mother's arms into the loving bosom of the

Savior who said, "Suffer the little ones to come unto me."

In the Flemish city of Antwerp in the Protestant corner of a Catholic

cemetery is a tiny grave wherein lie buried many happy anticipations for the

future, many bright hopes for Africa and her people.

***

I shall long

remember that last night on the steamer. Captain and crew went ashore leaving

no provision for the two lone women who stayed to watch beside a babe asleep in

death. Nor shall I ever cease to be grateful to the Flemish stewardess who said

in her broken English, "I stay with you, Madame." Together we washed

and dressed the tiny body and I wrote the sad news to the anxious father back in

Congo. I did not tell him of the doctor who preferred drinking and gambling

with sailors and traders to looking after a sick baby, nor of the Captain who

swore when he heard of her death (which added another to the five already

occurring at sea) lest his stock of Christian forgiveness and charity should

not bear the strain put upon it. How I had prayed as I saw the lifeless bodies

just thrown overboard without a word of prayer or ceasing of the ship's

machinery; and the dear Lord answered by letting me take her ashore the next

morning, after an undertaker had sealed her in a little metal casket, embalming

being unknown there at this time.

An elderly

Scotch minister, a tourist who boarded the ship at Teneriffe kindly accompanied

me to the cemetery for a little service. Everyone was kind. Some sent flowers

and one young woman loaned me her coat.

The thoughtful

Englishwoman, keeper of the hotel at which we had stayed on our way out, sent

an English speaking woman in her employ out shopping with me for some warmer

clothing; and I took the night boat across the North Sea and early the next

morning found our friend Mr. Robert Whyte waiting for me on the pier. This

gracious gentleman took me at once to his home, where, alas, I was obliged to

go to bed and remain there for several weeks, cared for as lovingly as a

daughter. When I was up and about again, a bit shaky, the doctor and the family

were unanimous in declaring that to return to Congo would be nothing short of

suicide for me and another little life as well; and being too weak both

physically and mentally to object, I let them arrange passage to America for

me.

Mr. Whyte sent

one of his trusted men to Liverpool with me to put me in a comfortable

stateroom on the Germanic, and speed me on my voyage home. Most of it was spent

in bed, not seasick,, but fever sick; and when we landed, Decoration Day, 1901,

I was escorted to the customs by doctor and nurse and a chair found for me. Mr.

Whyte had cabled my brother when I left England and he and my mother, in a

roomy carriage, were awaiting me. Being, as the doctor had said, "a nice

biscuit color" and scarcely able to hold up my head, my brother did not

recognize me until I alone remained and he was convinced that I must be his

sister. The authority kindly allowed the coachman to drive up to my chair and

we drove to my mother's home where I was put to bed. I shall always believe that

good Dr. O. S. Ritch, under God, saved my life, for having known me from a

child and being intensely interested in my Congo experiences he had taken

advantage of everything written about tropical diseases; and because of the

recently fought Boer War, medical journals were full of the subject. Certain it

is that I had what was called then, hemoglobinuric fever, Africa's worst; but

under his skillful administration I improved enough to go from hot Brooklyn to

cooler Kinston some 75 miles up the Hudson. There my second child, a boy,

Laurence Hasbrouck Snyder, a bouncing ten-pounder, was born, July 23, 1901.

This is the son with whom I am living now, once more in the tropics.

So one little

Heavenly bundle went back to its giver and another one was accepted in its

place.

Laurence grew

strong and active and our winter passed quickly. In March 1902 my husband came

home and made the acquaintance of his lusty son who quite refused to

acknowledge the relationship and spent a long time yelling his opposition until

he dropped asleep from exhaustion. When he awoke all animosity had gone, and

from thence forth the two were the best of comrades. As spring came Aunt Anna

returned to Pine Bush and my husband and I had an opportunity to rent a a house

in Maple Street, Brooklyn, and to borrow furniture from the Gilbert family who

were breaking up housekeeping. Accordingly we moved there, and Mabel Smedes, niece

of Ngangabuka, came to live with us, attend school and help me in the home.

Here we fixed up a room for Laurence in which, though only two, he took great

pride and would take visitors by the hand, saying to them, "Come see my

room." He never talked baby talk and his father treated him like a ten

year old. How much he owes to those early years and the companionship and

instructions of his father we cannot truly estimate.

Here on December

20, 1902, my second son was born and named Robert Whyte, after our good English

friend. Incidentally Laurence was named for my sister, Laura Hasbrouck Wood.

Robert was a beautiful healthy baby, thriving on Eagle Brand condensed milk. We

called him our little Bob Whyte. We lived near Prospect Park, and many days I

would pack a lunch, and we would all go to the Park for the day, the father

with his books or sermon writing , I with my sewing or mending. This outdoor

life did much for my health, enabling me to gradually throw off the

hemoglobinuric fever, although ten years passed before I was entirely free from

it.

As the time

approached when the year's salary from the Board of Foreign Missions would

cease, Ngangabuka secured a position as pastor of the Frankon Avenue

Presbyterian church which he served until 1905. In 1903 we moved to an

apartment on Lafayette Avenue and here came the third son, named for his father

with the order reversed in order to avoid "junior." He is Clinton De

Witt Snyder, now one of the accountants in the employ of the Western Electric

Company and head of an important department. Mabel Snedes had returned home and

an elderly widow, known to us as Aunt Emma, came to live with us in 1904. She

was a great help and was with us until blindness overtook her and I was obliged

to let her go. We spent that summer at Bloomington, New York, near the old

stone homestead of the Snyder sisters Rose and Lill.

In 1905

Ngangabuka was called to the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in Paterson,

New Jersey, where his sister, Fannie Smedes, lived. So we moved to E. 24th Street

to a warm-hearted Scotch congregation, where I took on Sunday School work

again, and had a large group of boys and girls to teach. How old fashioned our

methods used then would seem today! From 1906 to 1910 were hard years. The

salary was very small, the housework and the care of three lively small boys

very taxing on my limited supply of strength. I had been brought up to be a

neat and careful housekeeper and it did not occur to me to let things go

undone. Many a Saturday afternoon when the house was all in order for the

Sabbath I would throw myself down and cry from sheer exhaustion and say,

"I can never do it another week!" But we have the promise "As

the days thy strength shall be" and divine strength was given to carry on.

In 1907, after three and a half years of rest from child bearing my fourth son

was born, July 31, and named after a dear friend, a roommate in the Brooklyn

homeopathic Hospital who had been with me at Bob Whyte's birth and came to be

with me at this time. Although her name was Alezina Parsell she was always

known as Allie so this boy was named Allan Parsell in her honor. He was a

delicate baby, put on a formula by the doctor attending me, and did not begin

to thrive until I took him up to Kingston out of the city's heat and put him under

the care of Dr. Henry Van Hoovenburg who had officiated at Laurence's birth. We

went back to Eagle Brand milk which had proved so successful for his brothers,

and from that time he grew strong.

In Paterson the

boys went to kindergarten and Laurence later began grammer school and gave

promise of being an excellent scholar. I remember his kindergarten teacher

saying to me, "That boy isn't a bit interested in our games. All he wants

is to be learning something." Clinton begged so to go to school with his

brothers that the principal said to let him come even though under the age and

would have to repeat the work. We did, and he went through that training twice,

and seemed to enjoy it thoroughly.

Friends on

Staten Island, twelve miles down from the ferry at St. George, invited

Ngangabuka to come and preach in the little church, as the old pastor had

recently died; with the result that a call was extended to him. On January 1,

1911, we moved down to the largest haouse we had yet lived in, a very nice

parsonage with big vegetable garden. The salary was very small but there was no

house rent. The garden we managed quite nicely. The good folks around us shared

fruit with us. "Let the boys come and pick" was often heard, and the

summers meant much canning and jelly and jam making for me.

When Dr.

Demorest, president of Rutgers College in New Jersey, came to speak in Poet

Richmond Church one night I went down introduced myself and told him of an

ancestor, Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, who was Rutgers' first president. He was

much interested, telling me to be sure to send Laurence there, and promising

him a scholarship. From that time I began to accumulate a college fund which

consisted mostly of what I could make selling jellies and jam. I found that

people liked my orange marmalade and many a jar of that helped the fund along.

The boys all

attended the grammer school at Prince Bay and at twelve Laurence was ready for

the Curtis High School at St. George, graduating from there at sixteen, ready

for college.

The years at Huguenot

Park were happy, if very busy. In order to raise even the small salary of the

minister it was necessary to give an entertainment or a supper each month and

the supervision and training fell to my lot. We gave plays, concerts, and

lectures; and we were busy rehearsing for something, most of the evenings,

making quite a reputation for ourselves.

In 1911 my two

aunts, Eleanor and Gertrude, made us a long visit, and in 1912 Aunt Anna came.

Through the

influence of a parishioner the next spring I had the opportunity of working in

New York, doing proofreading on a catalogue brought out yearly. The salary was

very appealing, $18 a week, and Aunt Fannie Smedes came from Bloomington to

keep house for me and permit me to do this work. In the summer of that year,

1913, my mother came to live with me and in October she died a victim of cancer

endured with great suffering. I worked for the catalogue producers a second

winter but in October of that year Ngangabuka suffered a paralytic stroke just

after we had celebrated our wedding anniversary with the old friends from

Brooklyn.

For two months

during the summer of 1915 I moved my family to Bradley Beach, New Jersey, and

took charge of a summer camp one month for girls, one month for boys. Here I

had the delightful opportunity of hearing Bill Sunday preach and Homer

Rodeheaver play and lead the singing in that huge and crowded auditorium. The

summer at the beach did the boys good, their father got better, and things went

well, though Laurence had one spill from his bicycle which quite knocked him

out and bruised him considerably.

I have neglected

to mention Ngangubuka's connection for some years with the Brooklyn Board of

Education. Each winter season they provided weekly illustrated lectures or

concerts for adult audiences, and about thirty of these were on the experiences

undergone in the Belgian Congo. The income of these helped us out greatly and

even after his stroke they were given, though I often had to accompany my

husband when he traveled at some distance to give them. Once when alone he was

knocked down on a New York street and several slides broken and at last e

became unable to lecture acceptably any more. The next winter the Board gave me

the position of supervisor of the evening, introducing the speaker, keeping

unruly street boys quiet, and writing the records. In the meantime we moved

from the parsonage to St. George, and a young student came to preach in the

Huguenot Church. I remember so well the day we moved. It was on Ngangabuka's

birthday, April 17, 1918. My friend Helen Voute, then Mrs. Theodore s. Tenney,

came with a birthday cake. The pastor of the Brighton Heights Reformed Church,

Rev. Howard Brinckerhoff, came to call, and we all sat in the kitchen on boxes

and barrels and ate ice cream and cake. The position of visitor for this church

was offered to me, which I gladly took. I rented my extra rooms in the large

house on Central Avenue to several nice people.

On October 1,

1920, I became pastor's assistant in the Brighton Heights Church, serving nearly

nineteen years in that capacity, seventeen of them under the pastoral of the

Rev. Dr. John H. Warnsguis, who was very kind to me. His gifted wife and the

large congregation were exceedingly considerate, and many precious friendships

are still in close touch until this day.

The boys grew up

well and strong but each different from his brothers. Laurence full of energy,

always finding a job to do and doing it well; Bob with his more leisurely way

and his head always "buried in a book"; Clinton who always know where

things were and the proper use of them; and Allan whose hands and skillful

fingers were his great assets.

Laurence was

doing well in college, Bob and Clinton were in Curtis High School until my

brother convinced them that they should go to work to help their mother.

Although I did not approve, this was done. The boys secured positions in New

York, Allan graduated from P.S. 16 and entered Curtis High. Meanwhile Laurence

had met and fallen in love with a pretty Norwegian maiden, Miss Guldborg Herland,

who later became his wife. When he graduated from Rutgers in June of 1922, she

and I went together to the commencement exercises very proud of our college

graduate. Graduation from Rutgers led to additional study at Harvard University

and Christmas Day 1923 Laurence and Guldborg were married in the Brighton

Heights Reformed Church on Staten Island and after a wedding supper at

Herland's took a boat for Raleigh where he taught until the Ohio State

University invited him there and he moved his family in 1930. He had previously

received from Harvard University his doctor of science degree a month or more

before his twenty-fifth birthday.

One by one the

boys married. Bob in 1927 to Winifred Hekking whose sweet face he first noticed

in the subway as they traveled back and forth to business in New York. Clinton

was captivated by a charming young neighbor, Maybelle Chappelle whose mother

was a church friend of mine. Winsome Mary Honan won Allan's heart while they

were both in Curtis High School. When the last one went, September 21, 1929, I

gave up housekeeping and several times shared an apartment with friends,

keeping on with my work as pastor's assistant.

In January of

1939 I had an acute attack of arthritis which resulted in my resignation and

the giving up of the work I loved.

The first of

June I disposed of my furniture, went to Mary and Allan's for a month and the

first of July went on my first plane trip to Columbus, Ohio, to become a member

of Laurence's household. From Columbus we went to his summer home on south Bass

Island in Lake Erie where we remained for six months. Loving so near the water

increased my arthritis so on my birthday, 1939, Laurence brought me to Columbus

where I spent some months.

Later Laurence

bought a lovely house with delightful garden and fruit trees in Worthington two

miles away and here, away from the water, I became much better and was able to

resume some church activities, teaching Sunday School, leading meetings and

enjoying the women's organization and the Dorcas Circle where lasting

friendships were formed. Here in the little Presbyterian Church my two

granddaughters were married, Clara to Stanley P. Converse in 1945 and Margaret

to Donald L. Petersen in 1947. From there we all came east in 1947 to see

Laurence receive his honorary degree from Rutgers, his Alma Mater.

In 1947 Laurence

was invited to become Dean of the Graduate college of the University of

Oklahoma, so once again we moved, this time to Norman and to another large

house in a delightful town. It was my first experience of life in a college

town and I much enjoyed the many adventures it offered. This move brought many

new friends into my life and one of the great pleasures was the number of

elderly ladies who became the Maturitate Group and whose friendship still blesses

my life.

Here I was more

of less active in church work, the W.C.T.U. and the D.A.R., loving my

association with each one. They were eleven happy years and yet not without

pain. After several months of illness Bob slipped away from us to his Heavenly

Home and joined his sister and father. A household of wife, four daughters, a

seventeen year old son, and five grandchildren.

In 1958 Laurence

was asked to become President of the University of Hawaii, and later was

inaugurated with wonderful and impressive ceremonies. So here at almost the end

of life I find myself in the most beautiful of all my many homes, well cared

for, enjoying remarkable health for my age, still able to read, sew, quilt and

attend church, although I have need of a steadying hand when I try to walk.

The

grandchildren for whom this sketch has especially been written can pretty much

fill in any late details so it is unnecessary for me to recount them.

I am a most

grateful and proud mother, grand--and great-- because of my family of forty-eight.

I am ready to go at any time and sometimes I long to step across the border;

yet I still have a zest for life and appreciate all its blessings. Aloha to

you, my dear ones!

|

Would you like to go back...

or return to home page? click here. |