James D. Blauvelt discusses the Baylor Massacre; "OVERKILL"

OVERKILL: Revolutionary War Reminiscences of River Vale

by Kevin Wright

It was straight from the horse's mouth (so to speak) for James D. Blauvelt had "often heard his grandfather and Capt. Hering discuss the incident," telling how General No-flint Grey burst through the door on a moonless autumn night and how unarmed American dragoons, barely roused from sleep, had been bayoneted in his barnyard. James had already attained thirty years of age by the time grandfather Cornelius D. Blauvelt died in January 1832. Furthermore, James' father, David C. Blauvelt, had been a small boy, five years old, when the British bayonet-butchers came to call - and the horrific sights and sounds of that cold dawn must have left some impression upon his young mind and memory.

Even when grandfather Blauvelt had been dead and gone some four decades, James Blauvelt had no difficulty guiding his traveling companions about the

tragic scene, stopping by the wayside in the spring of 1872 and pointing to where the old stone house and its barn had stood and to where, beneath an

old tree shading a tannery in the vale of the Hackensack, five murdered Continentals had been laid to rest. Now it was Henry D. Winton, young editor

and proprietor of The Bergen Democrat, who did the listening, making notes as he went along. The result was a trilogy of articles encompassing local

reminiscences on Revolutionary War events on or about the old Blauvelt farmstead in the Overkill Neighborhood of River Vale, successively published

in The Bergen Democrat on May 31, June 21 and July 19, 1872.

tragic scene, stopping by the wayside in the spring of 1872 and pointing to where the old stone house and its barn had stood and to where, beneath an

old tree shading a tannery in the vale of the Hackensack, five murdered Continentals had been laid to rest. Now it was Henry D. Winton, young editor

and proprietor of The Bergen Democrat, who did the listening, making notes as he went along. The result was a trilogy of articles encompassing local

reminiscences on Revolutionary War events on or about the old Blauvelt farmstead in the Overkill Neighborhood of River Vale, successively published

in The Bergen Democrat on May 31, June 21 and July 19, 1872.

The Massacre near Old Tappan has been ably treated by historians over the past century. Acting upon the wise advice of historian Thomas Demarest, arch?ologists unearthed the skeletal remains of six Continental Dragoons in August 1967 from makeshift graves where they had lain since their hasty burial on September 28, 1778. Until now, historians have apparently remained unaware of this reminiscence of Cornelius D. Blauvelt, told through the mouthpiece of his grandson in 1872. It provides an immediacy lacking in most other sources and a perspective of the incident that is rich in character and detail. The two additional narratives are equally informative and unique. The Invasion of September 1778: Atrocity at Overkill.

When Sir Henry Clinton's army, six thousand strong, waded ashore at Paulus Hook on September 22, 1778, friends of American Independence were

wise to puzzle over his intentions, apprehending a decisive march northward along the Hudson River to "cut off the communication between the

Southern and Eastern states." The Continental army, reinforced by a large body of Jersey militia, kept just beyond reach of their deadly opponent

and alert for any sign of determined motion. The British swiftly advanced to New Bridge, dug in at Brower's Hill and stretched a defensive line

across the peninsula, eastward through Liberty Pole to the Palisades. By this means, "they confined themselves to a small portion of country,

between two navigable rivers, exposing only a small front, impenetrable by its situation, and by works thrown up for its further security." The

invaders then set about stripping the countryside of its fresh harvest and fattened cattle, engaging a fleet of about one hundred small vessels

to haul plunder down the Hackensack River. Some farmers thought that the devouring host seemed "much fonder of forage than of fighting."

Major Alexander Clough, stationed at New Bridge with the Third Regiment of Light Dragoons, engaged in the shadowy world of military intelligence

where distinctions between friend and foe often blurred. The regiment retreated to Paramus with the sudden appearance of the British army. After

four days assisting Bergen militiamen in driving cattle out of reach of British foragers, Colonel George Baylor moved his Light Dragoons from

Paramus to a spot where he might best gain immediate intelligence of any northward invasion. Accordingly, on September 27, 1778, Quartermaster

Benjamin Hart secured quarters for the six troops of Baylor's Dragoons in six different barns along the Overkill road (in what is now River Vale),

while Colonel Baylor made his headquarters at the dwelling of Cornelius A. Haring, about a half mile above a bridge over the Hackensack River. The

Dragoons drove some cattle with them and privates in the Third and Fifth Troops were posted as forage guards that night. The remainder of the men

bedded down in barns near their unsaddled horses. Although the Overkill Neighborhood was infected with Loyalists, the position seemed sensible and

secure, provided the usual precautions against surprise attack were taken.

wise to puzzle over his intentions, apprehending a decisive march northward along the Hudson River to "cut off the communication between the

Southern and Eastern states." The Continental army, reinforced by a large body of Jersey militia, kept just beyond reach of their deadly opponent

and alert for any sign of determined motion. The British swiftly advanced to New Bridge, dug in at Brower's Hill and stretched a defensive line

across the peninsula, eastward through Liberty Pole to the Palisades. By this means, "they confined themselves to a small portion of country,

between two navigable rivers, exposing only a small front, impenetrable by its situation, and by works thrown up for its further security." The

invaders then set about stripping the countryside of its fresh harvest and fattened cattle, engaging a fleet of about one hundred small vessels

to haul plunder down the Hackensack River. Some farmers thought that the devouring host seemed "much fonder of forage than of fighting."

Major Alexander Clough, stationed at New Bridge with the Third Regiment of Light Dragoons, engaged in the shadowy world of military intelligence

where distinctions between friend and foe often blurred. The regiment retreated to Paramus with the sudden appearance of the British army. After

four days assisting Bergen militiamen in driving cattle out of reach of British foragers, Colonel George Baylor moved his Light Dragoons from

Paramus to a spot where he might best gain immediate intelligence of any northward invasion. Accordingly, on September 27, 1778, Quartermaster

Benjamin Hart secured quarters for the six troops of Baylor's Dragoons in six different barns along the Overkill road (in what is now River Vale),

while Colonel Baylor made his headquarters at the dwelling of Cornelius A. Haring, about a half mile above a bridge over the Hackensack River. The

Dragoons drove some cattle with them and privates in the Third and Fifth Troops were posted as forage guards that night. The remainder of the men

bedded down in barns near their unsaddled horses. Although the Overkill Neighborhood was infected with Loyalists, the position seemed sensible and

secure, provided the usual precautions against surprise attack were taken.

Despite its ominous sound, the name Overkill derived innocently enough from a small bridge and hamlet lying "Over de kill" where several farmhouses,

barns and stables edged the main road to Middletown, New York. Several lateral roads (presently called Piermont Avenue, River Vale and Old Tappan

Roads) joined above the Overkill bridge, interlacing the Kinderkamack, Schraalenburgh and Tappan roads. The site was clearly strategic and presently

exposed to danger, for the British left was anchored on Brower's Hill at New Bridge, only nine miles south of the Overkill bridge.

The Dragoons needed to keep their ears to the ground. To secure their position in proximity to the enemy, Colonel Baylor personally "fixed a guard,

of a sergeant and twelve men" at the bridge to provide sufficient alarm of any approach of the enemy. This guard was posted with orders "to Patrole

a Mile below the Bridge, & at some Distance from the Roads - the Patroles were to be relieved every hour." A significant addition to the historic

record, provided by the Blauvelt tradition, is indication that this American guard was stationed at the Blauvelt farm, just above the bridge; the

men being quartered in the barn and several officers in the house. The Blauvelts recalled how: "Those placed on the bridge a little to the south of

the house left their positions early on the evening of the massacre and joined their companions in the [Blauvelt] barn saying it was useless for

them to keep watch as the night was so dark that the enemy could never find their way about. The American captain hearing their return ordered them

back to their places and they reluctantly obeyed his command. In a short time, however, they returned using their former arguments about the darkness

of the night and the difficulty of troops traveling." The return of the patrols at seemingly short intervals (as remembered by the Blauvelts) may

not reflect any fatal dereliction of duty, but only that the patrol was relieved hourly as ordered.

Despite its ominous sound, the name Overkill derived innocently enough from a small bridge and hamlet lying "Over de kill" where several farmhouses,

barns and stables edged the main road to Middletown, New York. Several lateral roads (presently called Piermont Avenue, River Vale and Old Tappan

Roads) joined above the Overkill bridge, interlacing the Kinderkamack, Schraalenburgh and Tappan roads. The site was clearly strategic and presently

exposed to danger, for the British left was anchored on Brower's Hill at New Bridge, only nine miles south of the Overkill bridge.

The Dragoons needed to keep their ears to the ground. To secure their position in proximity to the enemy, Colonel Baylor personally "fixed a guard,

of a sergeant and twelve men" at the bridge to provide sufficient alarm of any approach of the enemy. This guard was posted with orders "to Patrole

a Mile below the Bridge, & at some Distance from the Roads - the Patroles were to be relieved every hour." A significant addition to the historic

record, provided by the Blauvelt tradition, is indication that this American guard was stationed at the Blauvelt farm, just above the bridge; the

men being quartered in the barn and several officers in the house. The Blauvelts recalled how: "Those placed on the bridge a little to the south of

the house left their positions early on the evening of the massacre and joined their companions in the [Blauvelt] barn saying it was useless for

them to keep watch as the night was so dark that the enemy could never find their way about. The American captain hearing their return ordered them

back to their places and they reluctantly obeyed his command. In a short time, however, they returned using their former arguments about the darkness

of the night and the difficulty of troops traveling." The return of the patrols at seemingly short intervals (as remembered by the Blauvelts) may

not reflect any fatal dereliction of duty, but only that the patrol was relieved hourly as ordered.

Waiting for cover of darkness, the 2d Light-Infantry, 2d Grenadiers, 33d and 64th Regiments of Foot and fifty dragoons, under command of Major-General Charles Grey, stepped onto Kinderkamack road at New Bridge about ten o'clock on Sunday evening, September 27th. At about midnight, a second force under command of Lord Cornwallis marched northward on the Closter Road. This pincer movement was described as "a preconcerted plan with Sir Henry Clinton" who intended "to surprise some Light Horse and Militia lying in or near Tapaan."

As the British troops advanced northward on Kinderkamack road, they received "certain intelligence of the situation of the Dragoons, a whole regiment of which lay at Old Tapaan, ten miles from Newbridge." Precise information on the American cantonments and patrols permitted the British "to come unperceived within a mile of the place." Guided by local Tories who knew the ground, six companies of Light-Infantry under Major Turner Staubenzie passed to the rear of the American guard near the bridge, quartered on Cornelius Blauvelt's farm, "by going through Fields & bye-ways a great way about..." They approached their target between one and two in the morning. The remaining six companies under Major John Maitland halted for a time, allowing the others to get around behind the house and barn, then marched by the road, completing the encirclement, "by which maneuvers the Enemy's Patrol, consisting of a Sergeant and about a Dozen Men, was entirely cut off." By this stratagem and "without the slightest difficulty" the encircling British-Light Infantry "took or killed the whole guard without giving any alarm to the Regiment." The American guard was attacked with bayonets rather than musket fire, since the success of the British attack depended upon overwhelming the sergeant's guard "without any noise or alarm." At least one American sentry, however, escaped. The American officers staying at Blauvelt's house were captured without injury. Five Dragoons quartered in Blauvelt's barn were mortally wounded and, the next morning, these fatalities "were buried under the shade of a large tree in the vale opposite the house, near an old tannery which was in operation at that time."

Having destroyed the American sentries without raising any alarm, Major Staubenzie moved the 71st Light Infantry Company forward to surprise "a Party of Virginia Cavalry, stiled Mrs. Washington's Guards, consisting of more than an Hundred, commanded by Lieut.-Col. Baylor..." Private Samuel Brooking's account is indicative of the confusion and cruelty experienced by the startled Americans. He was bedded down in a barn with nineteen other Dragoons. Realizing that they were surrounded, they attempted to escape but were driven back by repeated stabbing. Those who then surrendered and marched out of the barn as prisoners were also bayoneted. Sam Brooking escaped through another door with a bayonet stuck through his arm and raced through the darkness to warn headquarters. Along the way, he repeatedly heard British soldiers shouting "skiver them, & give no quarters." He saw Colonel Baylor's headquarters surrounded by the enemy and so continued onward into the night, covering four miles to Paramus. Major Staubenzie's troops attacked Baylor's headquarters in the Haring house, seriously wounding Major Clough and Colonel Baylor with bayonet thrusts as they "attempted to get up a large Dutch Chimney..." Baylor's Adjutant, Lieutenant Robert Morrow, was stabbed seven times and knocked in the head with musket butts. Captain Sir James Baird's Company of 2d Light Infantry was then "detached to a barn where 16 Privates were lodged, who discharged 10 or 12 Pistols, and striking at the [British] Troops sans effect with their Broad Swords, Nine of them were instantly bayoneted and seven received quarter. "In 1876, one historian reported that the barn on the Haring farm "was standing until a few years ago, and it is said some of the posts and beams still retained the bloody evidence of British inhumanity." Major Maitland's troops, arriving at that time, proceeded to attack "the Remainder of the Rebel Detachment, lodged in several other Barns, with such Alertness as prevented all but three Privates from making their Escape."

As noted above, the six troops of American Dragoons were quartered in six different barns. Depositions from American survivors show that the barn

where First Troop slept was surrounded and taken by the 2d Light Infantry. Southward Cullency of First Troop reported that five or six of the wounded

were clubbed in the head with muskets upon Captain Ball's orders to "take no Prisoners." Cullency received twelve stab wounds.

As noted above, the six troops of American Dragoons were quartered in six different barns. Depositions from American survivors show that the barn

where First Troop slept was surrounded and taken by the 2d Light Infantry. Southward Cullency of First Troop reported that five or six of the wounded

were clubbed in the head with muskets upon Captain Ball's orders to "take no Prisoners." Cullency received twelve stab wounds.

The Dragoons of Second Troop, sleeping in a neighboring barn, were suddenly awakened by the cries of First Troop so that some of them managed to dress. Reaching the barn door, however, they realized that they too were surrounded by British soldiers and asked for quarters. Told to come out of the barn, they were stripped and robbed of their clothing and valuables. The British soldiers sent to Captain Ball in a neighboring house for orders - when the messenger returned, the Americans were herded back into the barn and bayoneted. Private Thomas Bensen was one of those awakened when he heard the dragoons of First Troop cry out that they were surrounded by the enemy. He was stabbed twelve times with bayonets, but managed to escape by jumping over the barnyard fence. Five men in his troop were killed. Private Julian King suffered sixteen wounds and Private George Willis suffered nine wounds. They heard the British soldiers send for Captain Ball to learn "what they were to do with the Prisoners, who returned for answer that they were to kill every one of them." After Thomas Talley of Second Troop was taken prisoner, he was stripped of his breeches and then ordered back into the barn, where he was bayoneted six times and left for dead.

Some privates of Third Troop were standing forage guard when they were surrounded by the enemy. After asking for quarters, they too were bayoneted. A corporal and three privates were left for dead. Corporal Henry Rhore managed to crawl back into the barn but died of his wounds the next day. Sergeant Thomas Hutchinson escaped unhurt.

Except for two guards on duty, the whole of Fourth Troop survived their capture without injury, owing entirely to "the Honour of Humanity" felt by an unnamed Captain of the British Light-Infantry who disobeyed orders and spared the captured dragoons.

James Arney of Fifth Troop was standing forage guard when his troop was surprised. Sergeant Sudduth of Fifth Troop told of being "awaked from his sleep by a noise among the men, & the first words he heard were kill them, kill them: upon which our men cried for quarters, & the enemy told them to turn out, & as they did turn towards the door of the barn the Enemy bayoneted them, & five of them were killed after they came out of the barn unarmed and with intent to surrender themselves prisoners of war." James Southward of Fifth Troop reported that "he escaped unhurt by concealing himself in the Barn which the Enemy entered - that there were 13 Men of his Regiment in the Barn, 5 of whom were killed outright, all the rest, except himself, were Bayoneted. - that he heard the British Officer order his Men to put all to Death, & afterwards, ask if they had finished all? That they offered quarters to some who, on surrendering themselves were Bayoneted." Bartolet Hawkins, a private in Fifth Troop, was also awakened when "alarmed by the Enemy." Unarmed and hopelessly surrounded by four British soldiers, he asked for quarters. One of their officers, however, ordered them to stab him. After bayonet thrusts from two British soldiers, he was left for dead on the ground near the barn door. According to Dr. Griffith, Barlett Hawkins of Fifth Troop suffered three wounds, two of them in his breast. Hawkins told Griffith that "after he got out of the Barn where he lay he asked for quarter, and the Officer called out to the Soldiers to Stab him which they immediately did. - That he heard the British Soldiers say they could give no quarters as it was contrary to their Orders."

Private Joseph Carrol of Sixth Troop, alarmed by the call of his sergeant, got up and quickly dressed. Surrounded by British soldiers as he went to saddle his horse, he asked for quarters but was stabbed with bayonets. The British soldiers, however, allowed four men of this troop, who tried to hide themselves in the straw, to surrender without subsequent harm. The rest of the troop escaped.

By tally of American surgeon David Griffith (as reported to Lord Stirling on October 20, 1778), the Third Regiment of Dragoons comprised 104 privates, "out of which Eleven were killed outright, 17 were left behind wounded, 4 of whom are since dead, 33 are Prisoners in N York, 8 of them wounded, the rest made their escape." The British soldiers lay upon their arms until daybreak, then marched onward via the Kakiat road, turning east and crossing the Hackensack River at Perry's Mills, thereby making their way to Tappan.

Which troop of American Dragoons was stationed in Blauvelt's barn? Contemporary evidence indicates that the guard consisted of thirteen men (not including officers stationed in the house). Cornelius D. Blauvelt related how: "On reaching the stable he found five men lying dead on the ground from wounds and many more seriously wounded. It appears only a portion of the English soldiers entered the house, the remainder being detailed for the bloody tragedy in the barn. The wounded ones received immediate attention and at night the others were buried under the shade of a large tree in the vale opposite the house, near an old tannery which was in operation at that time." James Southward of Fifth Troop reported "that there were 13 Men of his Regiment in the Barn [where he stayed that night], 5 of whom were killed outright, all the rest, except himself, were Bayoneted." James Sudduth of Fifth Troop also reported that five of his comrades were killed after they came out of the barn with intent to surrender. The correspondence of these numbers suggests that Fifth Troop comprised the thirteen-man Sergeant's guard quartered in Cornelius Blauvelt's barn that night and that the five fatalities of this troop were subsequently buried across the road at the tannery. The sixth burial at this place, evidently a sergeant, was likely posted on or near the bridge when he was killed.16 The other sentry escaped and reportedly reached the Haring House where Baylor and Clough were quartered.

The tradition handed down from Cornelius Blauvelt tells of an "American captain and doctor and other officers" who were captured in his house

that night, none of whom were wounded or killed in the attack. A count of those taken prisoners to New York, compiled by Dr. Griffith in October

1778, includes: Captain John Swan, Lieutenant Robert Randolph, Cornet Francis Dade, Cadet John Kelly and Surgeon's Mate Thomas Evans. Captain Swan

and Surgeon's Mate Thomas Evans were probably captured at the Blauvelt dwelling as were some or all of the remaining subalterns listed as prisoners.

The tradition handed down from Cornelius Blauvelt tells of an "American captain and doctor and other officers" who were captured in his house

that night, none of whom were wounded or killed in the attack. A count of those taken prisoners to New York, compiled by Dr. Griffith in October

1778, includes: Captain John Swan, Lieutenant Robert Randolph, Cornet Francis Dade, Cadet John Kelly and Surgeon's Mate Thomas Evans. Captain Swan

and Surgeon's Mate Thomas Evans were probably captured at the Blauvelt dwelling as were some or all of the remaining subalterns listed as prisoners.

David C. Blauvelt died in January 1835, aged 62 years, outliving his father by only three years. The inventory of David Blauvelt's possessions includes a general description of his house and outbuildings, presumably the same "large stone house" where he and his family resided in September 1778. His dwelling consisted of a garret for storing grain, flour, meal and feed; the "upper Room" outfitted with beds, cupboard, floor cloths, table and tea service; the "Lower Room" with brass clock, mirror, beds, chairs, tables, closet and other furniture; a cellar with barrels and casks for storing lard, butter, cider, vinegar, soap, apples and potatoes; and the kitchen with its meat casks, iron pots, lye cask and farming tools. David Blauvelt had a Blacksmith shop on the premises (probably located on the east side of the road near the old tannery), two barns and a saw mill (which apparently sawed both lumber and basket splints). The barn and barnyard contained horses, cows, calves, sheep, hogs, fowls, corn in the ear, harness, fodder, wagon, sleighs, sawed timber and a windmill. The other barn stored hay.

Lastly, we must recognize that there is a dark side to the Blauvelt narrative. In 1776, Cornelius D. Blauvelt was listed as a First Lieutenant in the Bergen Militia. Yet he was neither attacked nor taken prisoner on the night in question. An important part of the Blauvelt narrative tries to explain why "not a single cents worth of property" was plundered from Cornelius' house, despite the fact that American officers were found quartered there. The initial encounter between Mr. Blauvelt and General Grey almost sounds like an exchange of passwords: according to the narrative, when the British forced entry into his home and asked who he was, Lieutenant Blauvelt "coolly replied 'I am a man for my country and will fight for it till I die.' [General] Grey said he also was a man for his country and complimented Mr. Blauvelt for his patriotism." One wonders who it was that subsequently attempted to murder Cornelius D. Blauvelt - but the answer to this and to other questions have gone to the grave with the participants. Ironically, Captain Abraham Blauvelt of the First Regiment of Orange County Militia, who was surrounded by British troopers later that night and bayoneted, was Cornelius' older brother. His younger brother, Theunis, a Loyalist, was commissioned Captain in the Third New Jersey Volunteers and joined the Tory exodus to Nova Scotia at the war's end.

From The Bergen Democrat

May 31, 1872: River ValeLike its neighbor Mont Vale, River Vale experienced stirring times during the revolution which ended in the overthrow of British dominion and arrogance in this great republic. There are still many old people living in the neighborhood who relate incidents yet unpublished which they heard from the lips of those who took part in the struggle. On a recent occasion while driving in the neighborhood accompanied by G. F. Hering, of Mont Vale, and James D. Blauvelt, who is well acquainted with the history of the district, the horses were pulled up at the corner of the road leading from Hillsdale to River Vale and the main road to Middletown, and Mr. Blauvelt pointed out to us the place where the barn in which Col. Baylor's men were massacred, once stood. It was at the rear of a large stone house which was at that time occupied by Cornelius D. Blauvelt, the grandfather of our informant. Ramsey's History of the Revolution gives a graphic but somewhat exaggerated account of the bloody tragedy. Mr. Blauvelt often heard his grandfather and Capt. Hering discuss the incident and according to them the true account of the affair was substantially as follows: For some days previous to being surprised, Col. Baylor's regiment of Kentuckians were in the neighborhood and had suspicions that the British forces were at no great distance away. The officers made the house of Mr. Blauvelt their headquarters during their stay, their men finding comfortable shelter in the large barn at the rear.

To prevent against a surprise on the part of the enemy, soldiers were stationed on all the roads leading to the house and it is generally admitted that the

fact of one body of these men quitting their post was the immediate cause of the disaster. Those placed on the bridge a little to the south of

the house left their positions early on the evening of the massacre and joined their companions in the barn saying it was useless for them to

keep watch as the night was so dark that the enemy could never find their way about. The American captain hearing their return ordered them

back to their places and they reluctantly obeyed his command.

In a short time, however, they returned using their former arguments about the

darkness of the night and the difficulty of troops traveling. The Federal officers on being informed of this second dereliction of duty was

{sic} incensed and exclaimed "impossible!" and the word was scarcely spoken before the house was alarmed by a loud battering at the door and

a moment afterwards it fell in with a crash, the British soldiers under command of "no flint" General Grey rushing in and demanding a surrender

at the same time. The American captain and doctor and other officers there made no contention to the owner of the house, who in answer to

a question as to who and what he was, coolly replied "I am a man for my country and will fight for it till I die." Grey said he also was a

man for his country and complimented Mr. Blauvelt for his patriotism. During this conversation Grey's men were pillaging the house of all

the valuables it contained. A number of them were busy at an old dresser loaded with shining pewter ware eagerly filling their pockets with

the most portable articles, evidently under the impression they had valuable silver prizes, when Mr. Blauvelt turning to the General said,

"Is King George so poor that he has to instruct his soldiers thus to rob farm houses?" Grey was abashed and replied, "no, the soldiers have

no such orders and I won't allow them to disturb anything in your house." He then gave his men orders to disgorge which they slowly and

reluctantly did. Several times during the General's stay in the room Mr. Blauvelt's little son David who was then only six or seven years of age,

approached him and shook his fist in his face, and on each occasion was told to "go to bed you little devil." The "little devil" however remained

up till the British troops evacuated the premises which they did shortly after carrying away with them the American officers taken prisoners but

not a single cents worth of property. Whether Col. Baylor was in the house or not at the time of the surprise our informant could not positively

say, but one thing is certain he escaped the clutches of the enemy. In all probability he was in the neighborhood on the fatal night, as it is

generally believed he was wounded though not very seriously on the occasion.

In a short time, however, they returned using their former arguments about the

darkness of the night and the difficulty of troops traveling. The Federal officers on being informed of this second dereliction of duty was

{sic} incensed and exclaimed "impossible!" and the word was scarcely spoken before the house was alarmed by a loud battering at the door and

a moment afterwards it fell in with a crash, the British soldiers under command of "no flint" General Grey rushing in and demanding a surrender

at the same time. The American captain and doctor and other officers there made no contention to the owner of the house, who in answer to

a question as to who and what he was, coolly replied "I am a man for my country and will fight for it till I die." Grey said he also was a

man for his country and complimented Mr. Blauvelt for his patriotism. During this conversation Grey's men were pillaging the house of all

the valuables it contained. A number of them were busy at an old dresser loaded with shining pewter ware eagerly filling their pockets with

the most portable articles, evidently under the impression they had valuable silver prizes, when Mr. Blauvelt turning to the General said,

"Is King George so poor that he has to instruct his soldiers thus to rob farm houses?" Grey was abashed and replied, "no, the soldiers have

no such orders and I won't allow them to disturb anything in your house." He then gave his men orders to disgorge which they slowly and

reluctantly did. Several times during the General's stay in the room Mr. Blauvelt's little son David who was then only six or seven years of age,

approached him and shook his fist in his face, and on each occasion was told to "go to bed you little devil." The "little devil" however remained

up till the British troops evacuated the premises which they did shortly after carrying away with them the American officers taken prisoners but

not a single cents worth of property. Whether Col. Baylor was in the house or not at the time of the surprise our informant could not positively

say, but one thing is certain he escaped the clutches of the enemy. In all probability he was in the neighborhood on the fatal night, as it is

generally believed he was wounded though not very seriously on the occasion.

An archaeological excavation in 1967, cosponsored by the Bergen County Board of Chosen Freeholders and the Bergen County Historical Society discovered the burial site of Continental Dragoons. They were slain Sept. 28, 1778 and then buried in tanning vats. In the 1970s, the remains were reinterred at this site.

Also see the article in the 1971 BCHS Annual.

The Baylor Massacre site is open during daylight hours.

It was not until the next morning that Mr. Blauvelt discovered the full extent of the British brutalities. On reaching the stable he found five men lying dead on the ground from wounds and many more seriously wounded. It appears only a portion of the English soldiers entered the house, the remainder being detailed for the bloody tragedy in the barn. The wounded ones received immediate attention and at night the others were buried under the shade of a large tree in the vale opposite the house, near an old tannery which was in operation at that time. At this point the river is embosomed in green hills studded over with trees of every description and the flowing stream reflects their tall forms and waving branches, fully justifying the romantic title of River Vale. At the time of which we write, however, that name was unheard of, the district being known as Old Tappan. It has since been called Greenwood but only for a short space of time, it being objectionable on account of the celebrated cemetery bearing the same title. River Vale was substituted and is likely to be the name of the settlement till time shall be no more. But to return to our story.

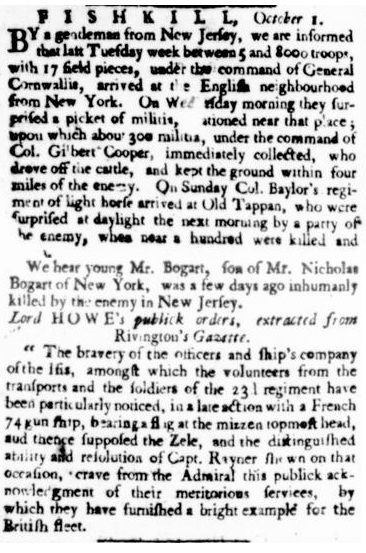

Virginia Gazette, Oct. 23, 1778

Colonial Williamsburg's CW Digital Librarydirect to the whole page

http://tinyurl.com/Baylor-Massacre

http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/BrowseVG.cfm

A curious incident is related in connection with the murder of the five men by Gen. Grey's soldiers. A few nights previous to the occurrence

Mr. Blauvelt was startled by hearing a noise in the rear of his house and on looking towards the barn he observed five lights near the door.

While viewing them in wonder as to what they meant, the lights suddenly moved towards the house and passing close by its walls crossed over

the street and down the embankment to the old tree near the tannery, where they suddenly disappeared. While passing the house Mr. Blauvelt

watched them closely but could not hear the least sound or catch a glimpse of any one carrying them - they seemed to move through the air as

if by magic. The circumstances made a deep impression on his mind at the time and he regarded it as a foreboding of evil. The sad sequel proved

that his misgivings were only too well grounded.

A curious incident is related in connection with the murder of the five men by Gen. Grey's soldiers. A few nights previous to the occurrence

Mr. Blauvelt was startled by hearing a noise in the rear of his house and on looking towards the barn he observed five lights near the door.

While viewing them in wonder as to what they meant, the lights suddenly moved towards the house and passing close by its walls crossed over

the street and down the embankment to the old tree near the tannery, where they suddenly disappeared. While passing the house Mr. Blauvelt

watched them closely but could not hear the least sound or catch a glimpse of any one carrying them - they seemed to move through the air as

if by magic. The circumstances made a deep impression on his mind at the time and he regarded it as a foreboding of evil. The sad sequel proved

that his misgivings were only too well grounded.It is conjectured that Grey's troops were led to the house by two notorious tories named Peter Ackerman and Peter Bogert. Circumstances occurred after the disaster which tended to the formation of this suspicion but no positive proof could be found. River Vale or Old Tappan was perhaps more infected by these wretched traitors to the American cause than any other place in Bergen County, and their hostility to those who rallied round the standard of Washington was even more intense than that displayed by the regular soldiers in the pay of Great Britain. They were enraged that Mr. Blauvelt escaped the death they had prepared for him when they acted as guides for Grey's bayonet butchers. On many subsequent occasions Mr. Blauvelt had to leave home and sleep in some other place during the darkness of the night to escape the knife of the prowling assassin. One night while he was in bed in his own house a loud knocking on his front door awoke him. A young man who was paying his address to his servant opened the door and had no sooner done so than a pistol was clapped upon his breast and a man in a mask demanded "Are you the master of the house?" The terrified swain with great presence of mind replied that Mr. Blauvelt had not been home since morning, and the would be murderer and his masked accomplices departed muttering curses on their ill luck. The troops who committed the outrage in the barn were some time afterwards captured by a body of American soldiers and they were all either shot or put to the sword. When they cried for quarter they were met with jeers and shouts of "Remember Old Tappan."

In a future issue [of The Bergen Democrat] we shall publish other interesting historical reminiscences relating to River Vale.

A second reminiscence of the Revolutionary War as related "by an old resident of River Vale" concerns an American soldier who accidentally stumbled upon a detachment of British soldiers who were quartered in a house and barn in the Overkill Neighborhood (possibly on the farm of Cornelius D. Blauvelt). This incident reportedly occurred "shortly after the murder of Colonel Baylor's men in Mr. Blauvelt's barn." While the editor of The Bergen Democrat does not name his source, it apparently is not Isaac Blauvelt. It is conceivable that this incident is a disassociated fragment of the story of the Old Tappan Massacre as heard and recalled by someone else in the neighborhood. It is perhaps significant that the English soldiers did not fell the escaping American with musket fire (so as to give alarm to others). Notably, the story-teller indicates that English troops were quartered in the house and barns, again, perhaps a mistaken interpretation of the facts. In any event, the story is similar to contemporary accounts told by the few who escaped Baylor's Massacre, for instance: "Captain Stith being suddenly surrounded by the enemy's horse and foot, and seeing no probable way of getting off, called out for quarter; but they, contrary to the rules of war and to every sentiment of humanity, refused his request, called him a damn'd rebel, and struck him over the head with a sword - which fired him with such indignation, that he bravely fought his way thro' them, leaped over a fence, and escaped into a morass." While escaping from another of the barns that night, Private David Stringfellow got forty or fifty yards before he was wounded by a small sword. He "fell down with the wound, & got under the feet of our own horse in a little shed to protect himself by that means from the farther assaults of the enemy, & there remained, till day light..." Here follows the story in its original length.

From The Bergen Democrat, June 21, 1872:

Reminiscences of River ValeA good anecdote of how a patriot soldier served a red-coat during the time of the revolutionary war was recently related to us by an old resident of River Vale, and we print it for the benefit of those of our readers who take an interest in such matters. It appears that shortly after the murder of Colonel Baylor's men in Mr. Blauvelt's barn, an account of which we published a few weeks ago, a detachment of British troops arrived on the ground and made the house and barn their head-quarters. An American soldier who was out foraging or reconnoitering in the neighborhood was in happy ignorance of the circumstance and walked unsuspectingly into the yard. The first intimation he had of the close proximity of the enemy was the sight of a large powerful looking Britisher making for him sword in hand. How to get out of the trap was the question. It would not do to show fight for English soldiers never traveled alone in those days. If he wanted an assurance of that fact he had it in the hum of voices which came from the outbuildings. And if he attempted flight he exposed himself to the danger of being riddled with shot. However, there was no time to think about the matter, and he took to his heels in hopes of reaching the woods, where the English dare not follow. At the end of the yard was an old apple tree and once round that he knew he was safe. But his pursuer also took in the situation at a glance and made a straight line for the tree. They reached the spot almost at the same instant, the American dodging round on one side to escape and the Englishman on the other to intercept him. While behind the tree the patriot whipped out his sword with the rapidity of lightning and just as he met his assailant dealt him a fearful blow on the crown of the head which had the effect of stretching him out insensible on the greensward. He then bounded into the woods and made good his escape before the men in the barn had time to raise their muskets.

The old apple tree has long since gone to decay, but the stump still remains a monument to the prowess of a patriot.

The farmstead of Cornelius D. Blauvelt is again the scene for the third remembrance of the Revolutionary War published by The

Bergen Democrat in 1872. In this case, the story deals with a troop of Indians who visited the Continental encampment at

Steenrapie (River Edge) on September 13, 1780. James Thacher, a Surgeon in the Continental Army, included the following description of

this incident in his Military Journal of the American Revolution:

"13th. - The army was paraded to be reviewed by General Washington, accompanied by a number of Indian chiefs. His Excellency, mounted

on his noble bay charger, rode in front of the line of the army, and received the usual salute. Six Indian chiefs followed in his train,

appearing as the most disgusting and contemptible of the human race; their faces painted of various colors, their hair twisted into bunches

on the top of their heads, and dressed in a miserable Indian habit, some with a dirty blanket over the shoulders, and others almost naked.

They were mounted on horses of the poorest kind, with undressed sheep skins, instead of saddles, and old ropes for bridles. These bipeds

could not refrain from the indulgence of their appetites for rum on this occasion, and some fell from their horses on their return to

headquarters.28 This tribe of Indians is friendly to America, and it is good policy to show them some attention, and give them an idea

of the strength of our army."

From The Bergen Democrat, July 19, 1872:

Reminiscences of River Vale.In our last article on River Vale, we gave an historical anecdote relating to the exploits of one of Washington's soldiers during the stay of the American army in that portion of our county. The scene, it will be remembered, occurred in the farm yard of Mr. Cornelius Blauvelt, who resided on the road leading from Hillsdale to Middletown, N. Y. This same old farm yard was the scene of another incident of the most ludicrous character, in which the "Poor Indian" played a prominent part. The Tappan tribe of Indians was known as a brave and resolute race, and the Americans determined if possible to enlist them on their side against the British. For this purpose, a deputation consisting of fifty or sixty noted braves, were invited to visit Washington's Camp, at Kinderkamack, where a large display was to be made to rouse their enthusiasm. On their way to Kinderkamack they had to pass the house of Mr. Blauvelt, who kindly invited them in to partake of refreshments. The red men gladly accepted the offer, but it was evident from their disappointed looks after dinner there was a something yet wanting to satisfy their desires. Mr. Blauvelt knew whiskey was the trouble, and he had not a drop in the house, his last keg having been emptied to gratify the wants of the soldiers. He approached one of the braves and led him to a corner of the yard where the empty keg lay, and pointing to it expressed his sorrow that the liquor was all gone. The Indian looked downcast for a moment, but his eyes soon began to sparkle, and seizing the barrel he summoned his comrades around him. He explained to them how matters stood, and gave it as his opinion that the proper thing for them to do was to make the best of a bad bargain. He then pointed to the barrel, and raising it to his face, he dipped his nasal organ into the bung-hole, and regaled his olfactory nerves with the sweet odor of the beloved "fire-water." Dropping the barrel when satisfied, he commenced a sort of festival break-down round the yard. The other chiefs followed the leader, each one smelling the bung and joining in the dance. When all had smelled to their hearts' content, the barrel was placed in the middle of the yard, and the chiefs, ranging themselves in order, performed a parting thanksgiving step around it, and resumed their journey to Kinderkamack, where more substantial stimulants were awaiting them.

On their arrival at Washington's Camp, they were allowed all the drink they desired, and afterwards taken out to witness a review of the troops. Everything was made as grand as possible, and the deputation were so impressed with the firing off of the heavy artillery that they went home vowing that "England had no chance with Mr. Washington, who would blow them all up." Of course the whole tribe went with "Mr. Washington," and the prophecy of the deputation was realized.

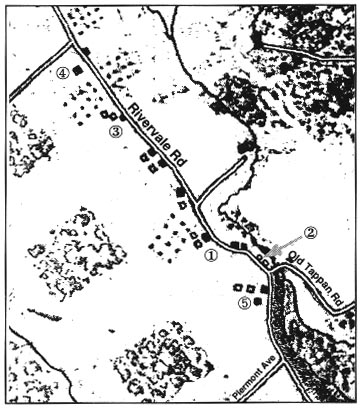

About the Maps, in the order they appear: 1. US Coast Survey, 1840 This map indicates both dwellings (solid blocks) and barns (open blocks). Note out buildings standing east of River Vale Road and northwest of the River, on the site of the old tannery - one of these may have been David D. Blauvelt's blacksmith shop. Was the other associated with the tannery? 1. Dwelling of Cornelius D. Blauvelt in 1778. An inventory of his son David's estate (1835) mentions two barns. 2. Tannery where Dragoons were buried. 3. Farmstead of Cornelius A. Haring where Baylor and Clough were headquartered.

4. (Peter?) Bogert Dwelling in 1778. 5. Farmstead of Abraham Johannes Blauvelt, brother ot Arie Blauvelt (the cordwainer believed to have started the tannery). 2. Erskine #113, 1780, Cornelius D. Blauvelt's dwelling is shown just north of the Overkill Bridge. The next dwelling to the southwest belonged to Abraham J. Blauvelt. Six dwellings are shown along the west side of River Vale Road between the intersections of Prospect and Piermont Avenues. 3. Map of the Baylor Massacre Neighborhood by Claire Tholl, originally done for Relics (Nov 1967) and reproduced in Bergen County History 1971 Annual. Note: footnotes removed.